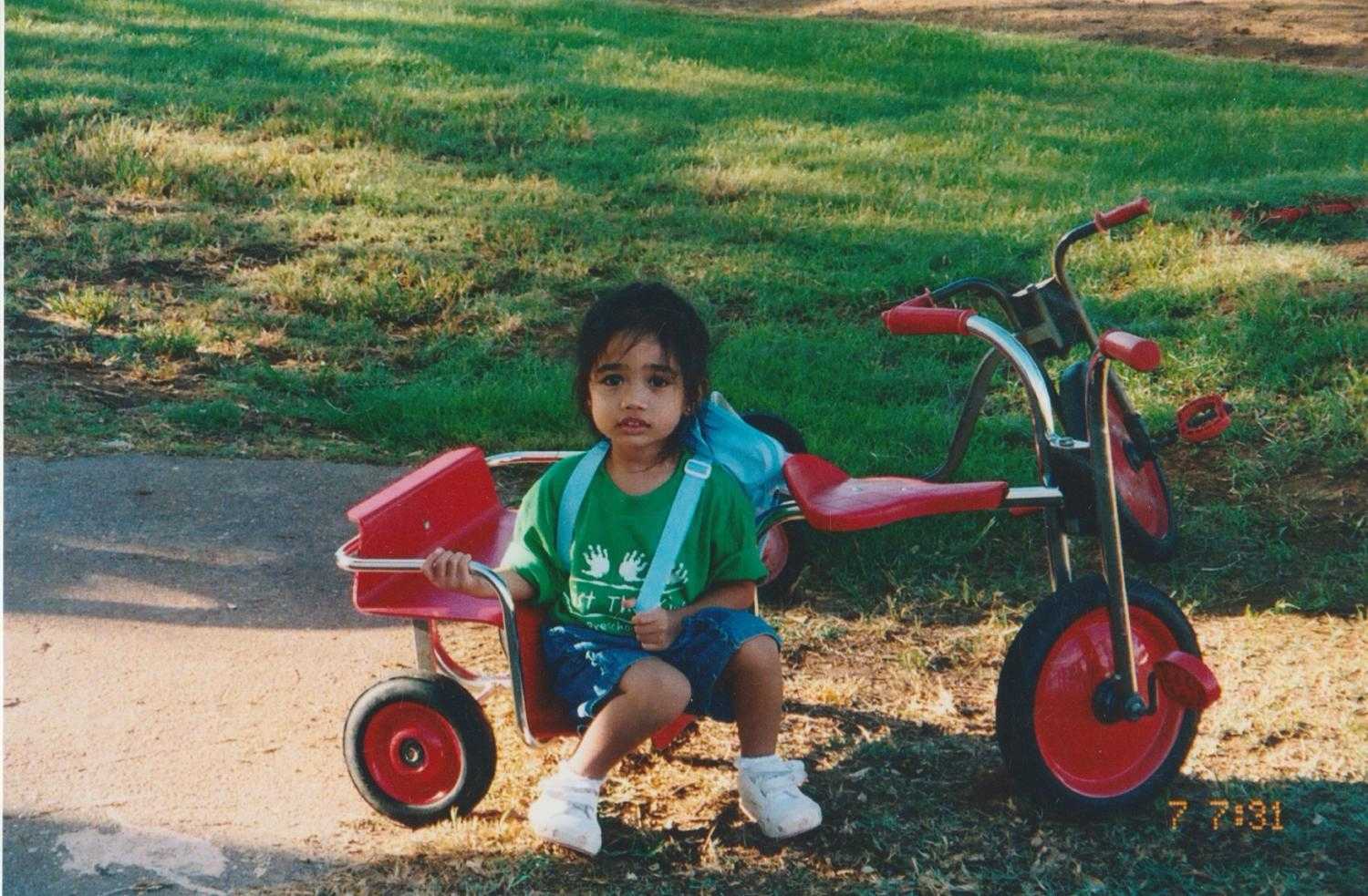

Sunday morning. Waffles drenched in store-bought maple syrup, I fit as many pieces as I can in my mouth as voices pass over my head. My mom and grandma talk as if I am not here, slurring unfamiliar words that make the slightest bit of sense. My tongue doesn’t recognize the language, though it’s rooted in my ancestry.

I experience my heritage the same way it feels when someone stands up too fast and gravity suddenly rushes against them. I am quick to take pride in my culture—easily overcome by a burst of confidence when the occasion calls. However, I speak through brief memories, recalling as much as I can with as little as I own. I cling to an identity I can barely prove to myself, but I don’t blame my parents.

In many foreign eyes, the United States is idealized and seen as a hub of bustling opportunities. The chance to pursue a positive future is what makes this nation popular among immigrants. With a free market economy, lower inflation rates, and ranked in the top 30 of educational performances worldwide, this nation is seen as promising to those who are struggling.

Unlike some countries, the United States takes pride in being multicultural, welcoming those who wish to stay. Home to immigrants from countless ethnic groups, people find a community to identify with and organize celebratory events to commemorate their heritage. They attempt to mimic traditions as closely as they can, but it fails to feel the same. Moving to the United States, “you win some, you lose some”—while there are benefits, it takes a toll on generations that follow.

As a second-generation Filipino-American, I only find small traces of my lineage scattered across my house. From the rice cooker hidden behind a stack of fruit to the instant pancit canton noodles on the shelves of my pantry, the signs are hardly existent when covered by a wall of processed cereals and a living room filled with modern decor. Succeeding generations can’t help but distance themselves. It’s a collaborative effort between societal influences and parental preferences.

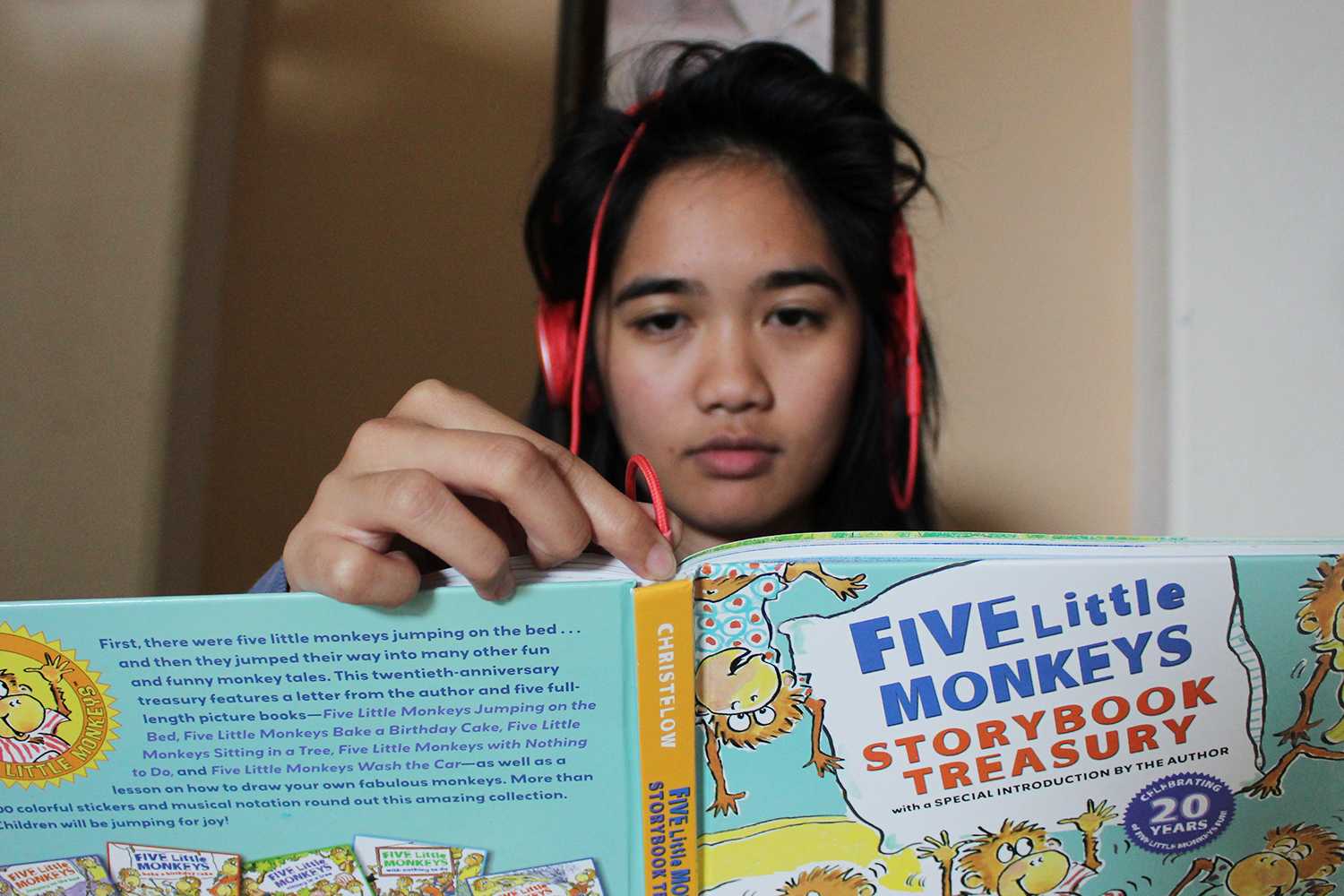

Growing up in a world dominated by the English language, teaching a second language often becomes irrelevant. Parents don’t prioritize their native tongue, assuming their child will have no use for it in the United States. More importance is placed on surviving in an English oriented country than surviving through cultural legacies. My family has caved so much into the dominating society that I’m left with little more than a few curse words in the back of my mind or lyrics to songs in Tagalog that I memorized for the sole purpose of karaoke nights with my grandparents.

There’s a never-ending expectation to uphold—fitting in with everyone else. In school, expectations are controlled by a stigma about differing from what is common. Whether it’s the accent that carries one’s words or the clothes that one is most familiar with, unconventional features lead to questioning stares and growing embarrassment. It promotes a disassociation with one’s ancestry so much so to the point of complete unawareness. If asked about one’s ethnicity, the only thing to offer is the name of a country without context.

To truly recognize the significance of individuality, it is important to claim the history behind one’s last name.

The fear of being different can spark from something as simple as home-brought lunch. In first grade, I used my lunch box as a wall hoping the kid with a sandwich next to me wouldn’t notice the smell of soy sauce. In third grade, a teacher worried over my pink-tinged rice and stopped me from eating before a Filipino teacher had to reassure her it was safe. Discouraged by the misunderstanding, I spent the next couple of years relying on school pizza.

Taking pride in what sets one apart becomes increasingly difficult, but is it worth it to form barriers that restrict self-identity? Absence of a culture means absence of a piece of oneself. To truly recognize the significance of individuality, it is important to claim the history behind one’s last name.

Getting older, I began to regret my efforts in washing out my culture. My identity feels like it’s missing key factors. At this point, blood is just blood—a nation nothing more than a label. The color of one’s skin isn’t the only thing to be inherited. It’s about being connected to the entire culture itself and tying it into one’s identity.

As an immigrant family assimilates, traditions dwindle and priorities shift. There is wealth in being aware of all aspects of yourself. Take in heritage with open arms, appreciating everything offered without remorse.

[poller_master poll_id=”13″ extra_class=””]

![Weighing her options, senior Allyana Abao decides between going on a practice drive or calling an Uber. Though unlicensed, Abao has considered driving to be a significant milestone of teen independence despite alternatives that provide much easier solutions.

“You're able to be independent and not rely on others,” Abao said. “You're able to get a job, get things that you need, go places you need to go. I have so many places that I want to go to and I ask [my family] for so much. I want to be independent to where they know that I can do things on my own, so they know that they don't have to be there for me.”](https://southwestshadow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_2922-1200x900.jpg)

![Looking at the board, former BSU secretary Christina Altaye begins to prepare for BSU’s second year of Club Feud. This year, “Are You Smarter Than a Ninth Grader?” will be replacing this event. “I think it’s a fun change [to Club Feud],” BSU Activities Director Hellen Beyene said. “[I think] it’s always fun to do something new and different.”](https://southwestshadow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-09-29-11.06.43.png)

!["I will be attending Trunk or Treat [for FCCLA]" junior Crystal Li said. "We're gonna use Mr. Harbeson's car, and we will be [hosting three different activities]."](https://southwestshadow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_0980-1200x900.png)