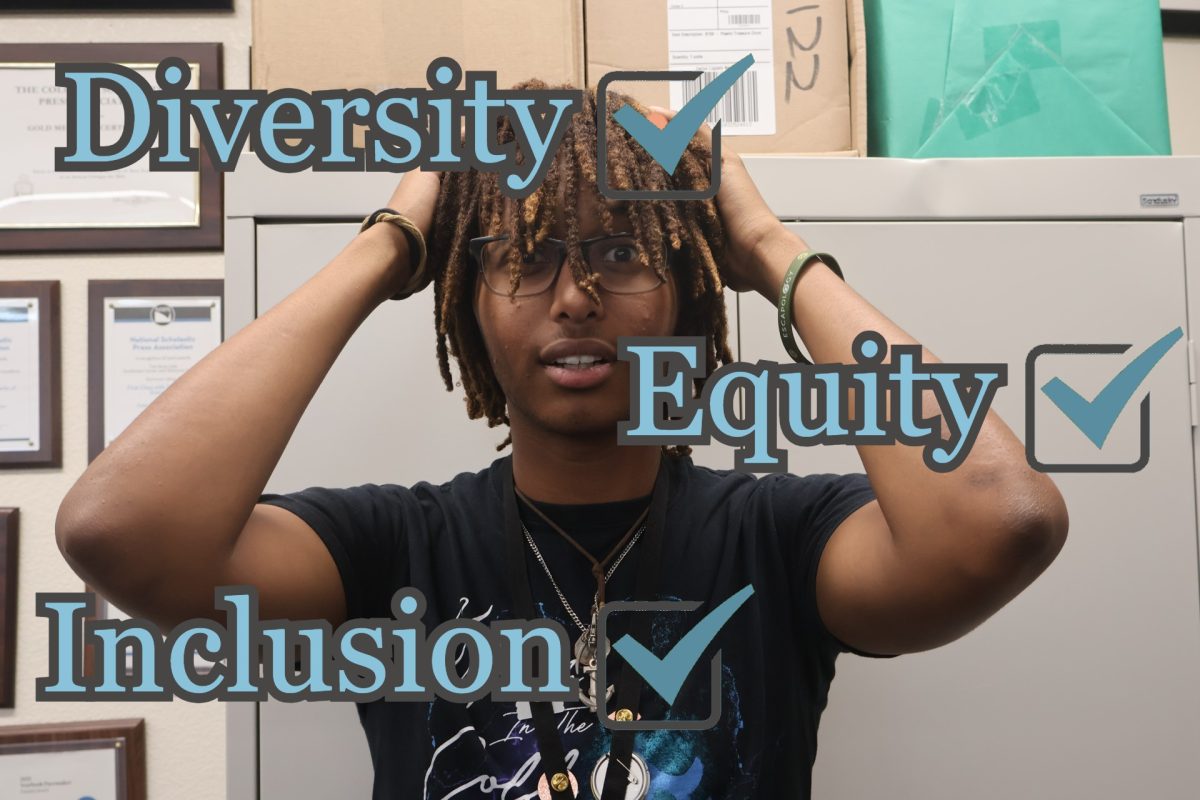

I was six years old when I first tried making friends. I still remember her pointing her daggers at me––like I was a criminal invading her home, as she spat “I am not friends with Black girls.”

From that moment on, it became pretty clear to me that the world was not ready to accept me. Since that day, I dedicated my life to try to avoid being a stereotype. I refused to listen to rap music, I never wore my natural curls, I avoided watermelon at all costs and could never be caught smelling like cocoa butter. Worst of all, I used to think if I scrubbed hard enough in the bath that maybe my Blackness would wash away.

It never did.

But every friend, teacher or acquaintance I had made it seem like I was superior for “not being like other Black kids”––as if it made me a better person to have had “whitewashed” myself. It was unsettling, but for so long I accepted it––because I would rather filter out parts of who I was than face the fact that there are people out there that hate me for something I can’t control. I became so obsessed with “not being Black” that I failed to realize that nothing I do will ever change the fact I am.

But as I began to unravel how wrong I was to be ashamed, I realized that this internalized hatred that many Black individuals share is not a reflection of how we really feel, but more of a reaction to the world around us.

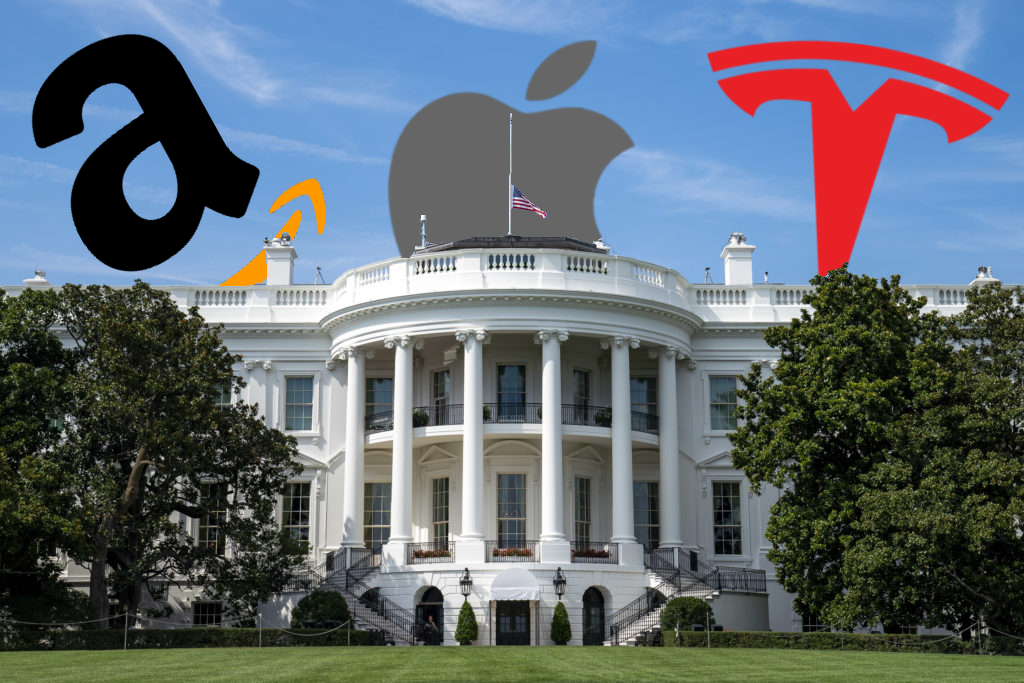

If you type into Google “four teenagers” and look at the images that were provided you would see many stock images of white teens being innocent and pure. But when you include the word Black into the search bar, the innocence is no longer there. Instead, the screen is filled with mugshot after mugshot of a few young Black teens who were caught up in crime, drugs or gangs.

Our world accepts the idea that being white is associated with being pure and that being Black means you are dangerous or up to no good. The issue is not that young Black kids, like me, are necessarily insecure, but rather that the internalized racism within our society has never given us a chance to be anything more than fixated stereotypes. The internalized hate is only a response to constantly being represented as angry, evil and dangerous people.

But being Black does not mean I am inescapably dangerous, evil or angry. I am ashamed to have ever thought that by being “less-Black,” I was a better person. The truth is regardless if I listen to rap, eat watermelon, wear my natural Afro and smell like the sweetest cocoa butter, it doesn’t make me any less of a human than the next guy––and will never change the fact that I am Black. No one should feel ashamed for being true to themselves or even for loving the beautiful skin that they have. I hope I live to see the day that our internalized hate isn’t so normalized.

I want to live in a world where young Black kids on the playground trying to make friends never experience the rejection I did, and never second guess their abilities or worth for something about themselves that they cannot control.

![Weighing her options, senior Allyana Abao decides between going on a practice drive or calling an Uber. Though unlicensed, Abao has considered driving to be a significant milestone of teen independence despite alternatives that provide much easier solutions.

“You're able to be independent and not rely on others,” Abao said. “You're able to get a job, get things that you need, go places you need to go. I have so many places that I want to go to and I ask [my family] for so much. I want to be independent to where they know that I can do things on my own, so they know that they don't have to be there for me.”](https://southwestshadow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_2922-1200x900.jpg)

![Looking at the board, former BSU secretary Christina Altaye begins to prepare for BSU’s second year of Club Feud. This year, “Are You Smarter Than a Ninth Grader?” will be replacing this event. “I think it’s a fun change [to Club Feud],” BSU Activities Director Hellen Beyene said. “[I think] it’s always fun to do something new and different.”](https://southwestshadow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-09-29-11.06.43.png)